Birds and Beasts in the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp[1]

The illustrations of the extraordinary Shahnama produced for the Safavid king of Iran, Tahmasp, between around 1524 and 1535, serves as a veritable compendium of the world of the early Safavids. The subject of an exhaustive monograph by Stuart Cary Welch and Martin Dickson, published in the 1981,[2] the manuscript has now come back into focus with the publication of a near-facsimile of its 258 illustrations in 2011 and a smaller version with some additional information in 2014.[3] In the 2014 book, I wrote an essay on the material world of Shah Tahmasp in which I identified a range of objects that are the sixteenth-century or later equivalents of those depicted in the paintings. I also drew attention to certain things that are described in eye-witness accounts of Tahmasp’s court but are no longer extant.[4] In addition to making the point that the artists of the Shahnama employed the costumes, architecture and accoutrements of their own time to depict those of pre-Islamic Iran, I touched on the question of the extent to which the artists based their compositions and the details within them on earlier works of art. While some of the compositions relate closely to those of Timurid painting of the fifteenth century, the manmade objects in the paintings are naturalistic renderings of the stuff of early Safavid life, from torches and turbans to fountain spouts and flutes.

In this paper I will discuss the depiction of animals in Tahmasp’s Shahnama in order to explore whether, like the material culture represented in the manuscript, the animals are depicted naturalistically and as if from life or if they are based on earlier pictorial prototypes. Additionally, I shall consider whether the animals in the paintings are or were native to Iran. Some, such as lions, became extinct in Iran only in the 1940s. Whether Tahmasp’s artists ever saw a lion in the wild again begs the question of to what extent they were painting only from visual models and if so, what those might have been. Although some animals in the Shahnama illustrations play a role in the text, others appear almost as props or to enhance the atmosphere of a scene as a whole. Thus, horses appear in 193 of the 258 illustrations, singly or in groups. Some have names and specific roles in the narrative, some are the mounts of the cavalry in battles, and some simply stand ‘parked’ and waiting for their owner, in the way today our cars sit outside until it is time to go. While some of these will be considered here, I will focus more on a range of other animals, in part to imagine Iran’s environment before the twentieth century and also to draw attention to the long tradition of depicting animals in many different media. As well as occupying the same space as the human protagonists in the Shahnama illustrations, animals also appear in wall paintings on the interior of buildings in the manuscript. A few of these will be discussed with an eye to how the approach to animals used as decoration differs from those which are part of the natural setting. Finally, the stories of the Shahnama include various encounters with fabulous beasts, which one can assume the artists imagined or copied but did not see, except perhaps in dreams.

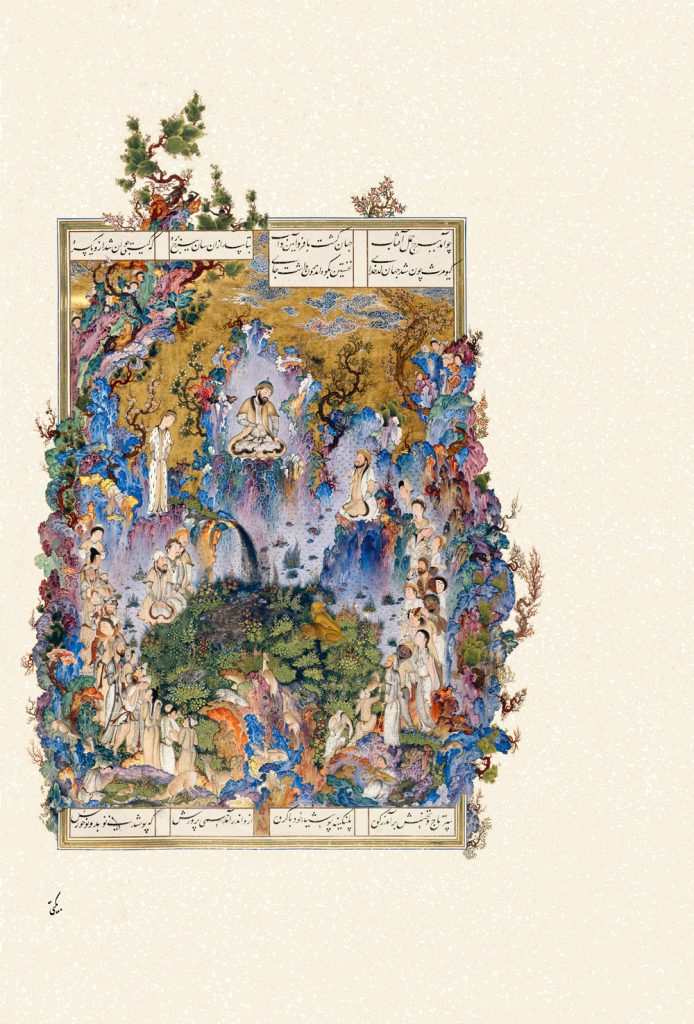

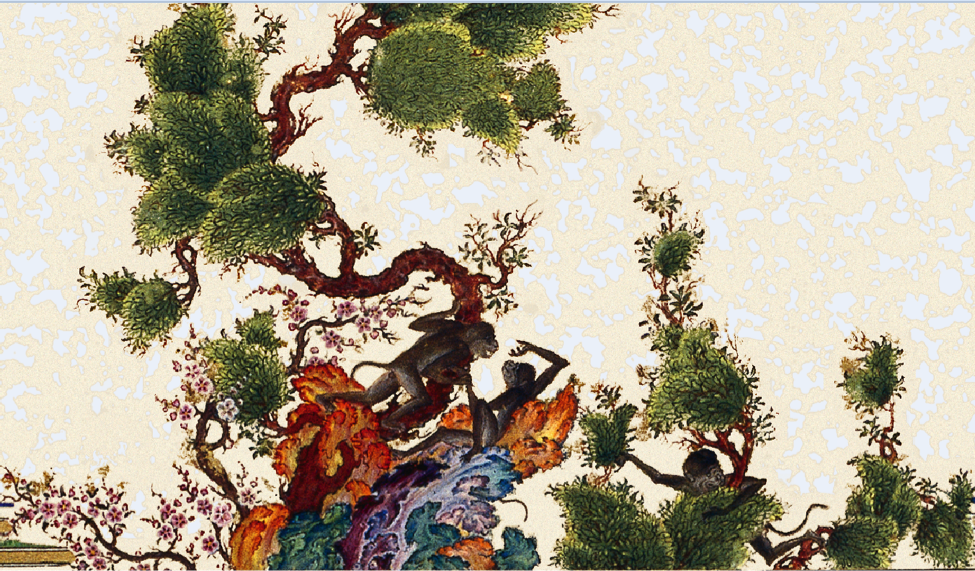

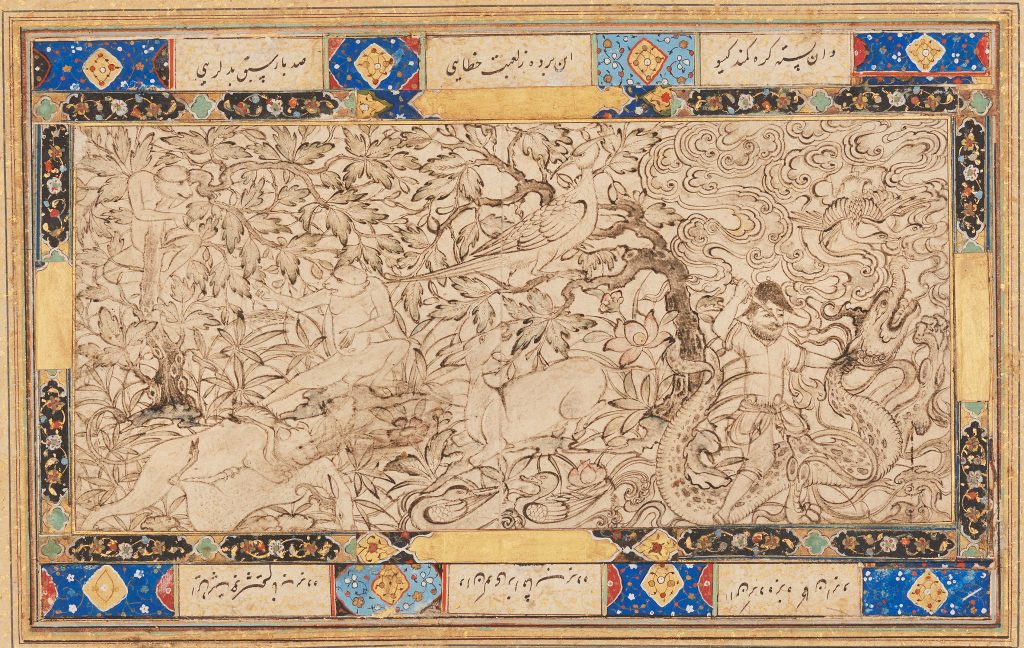

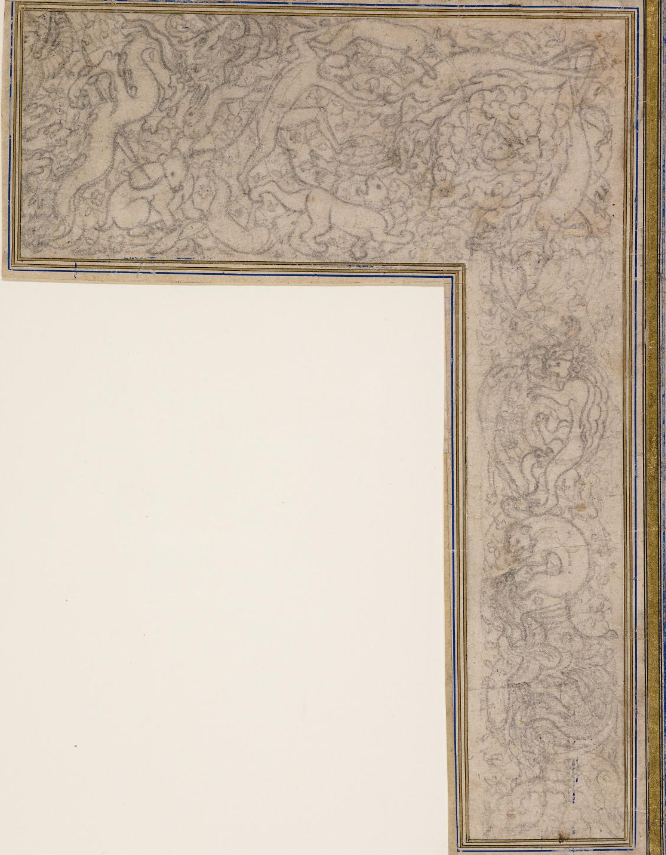

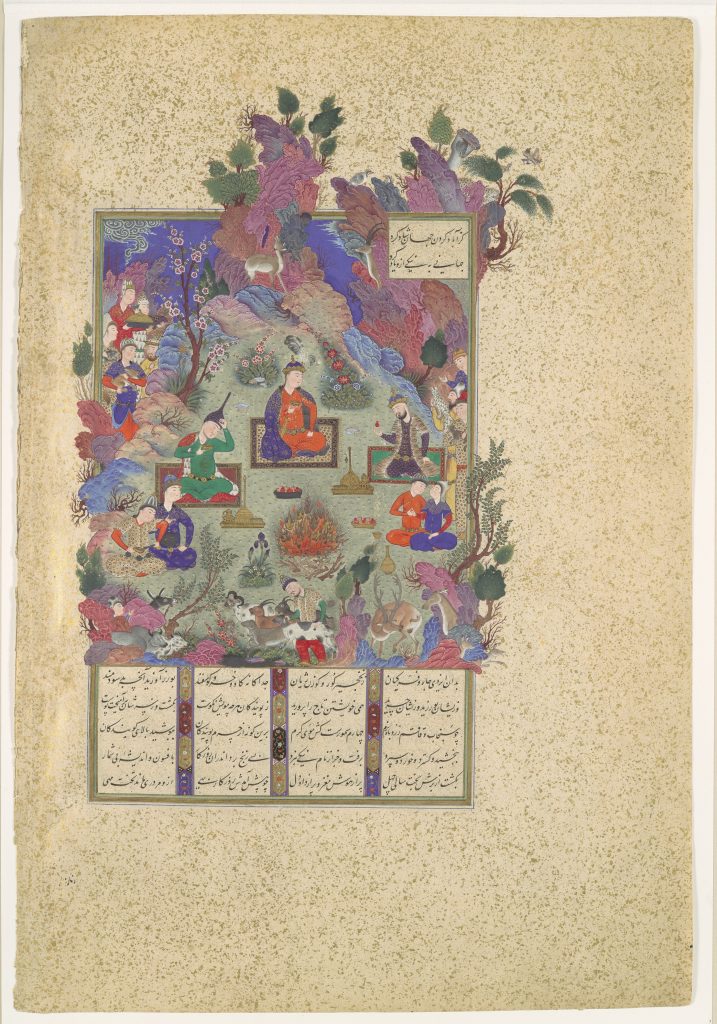

The first king of Firdausi’s Shahnama, Gayumars lived on a mountain and oversaw the development of the ‘arts of life’ His subjects all wore leopard-skins, as seen in “The Court of Gayumars” (fig. 1) and ‘The cattle and the divers beasts of prey/grew tame before him…’ In this remarkable painting attributed to Sultan Muhammad, the Tabriz artist who taught Shah Tahmasp painting and is assumed to have been the first supervisor of the Shahnama project, the cattle mentioned in the text are not immediately evident. Instead, lions, gazelles, deer, foxes, bear, a snow leopard and even monkeys appear singly and in pairs, peacefully coexisting. (Fig. 2) A closer look, however, at the clouds in the upper left reveals a cow and bull lying side by side. Furthermore, the rocks are alive with hidden faces, mostly of humans although some animals may be lurking here as well. A detail (Fig. 3) of the vegetation that extends beyond the upper margin contains three monkeys having fun in the trees. Since monkeys are not native to Iran, Sultan Muhammad would have known them from pictorial sources. One possibility is the picture albums of drawings and paintings, apparently compiled in the 15th century and containing a broad range of images of the type that were used in various media, including textiles and manuscript illustrations. (Fig. 4) Although not in the same poses, the two monkeys in a drawing of animals and a dragon combat from the early 15th century resemble those in the painting in type, which may be an Indian Bonnet macaque. In both images the monkeys jabber and gesticulate excitedly. In the design for a border from one of the Diez albums in Berlin (Fig. 5) a monkey in the same pose as the one on the left in the Shahnama painting grabs the foot of a fantastic beast that combines elements of a dragon and a griffon. Writing at the end of the 16th century, the artist Sadiqi Beg described the desirable traits in depicting animals. Stating that an artist should seek originality in portraying humans, he notes “But it is otherwise if your aim in figural painting is that of animal-design…For in this genre the shifting values of observation are not a desideratum; instead a solicitude for past models is at a premium. There is no swerving here from the principles established by the masters of old; here artful imitation (tatabbu‘) is the way that must be pursued.”[5] Thus, while artists may have borrowed compositions from earlier examples, only in the representation of animals could they admit to relying on a visual repertoire handed down from generation to generation. Manuscripts themselves, such as the illustrated 1429 and 1431 Kalila wa Dimna manuscripts produced for the Timurid prince Baysunghur,[6] would also have been of interest to Safavid artists seeking inspiration for their depictions of animals. These manuscripts would have been transferred from the Timurid royal library in Herat to the Safavid royal library where Sultan Muhammad worked. In addition, since Tabriz had been a capital of the Il-Khanids in the late 13th and early 14th century and the Jalairids in the mid-to-late 14th century, the Safavid royal library would also have contained manuscripts that had never left Tabriz. Although in the 17th century some evidence points to the Safavid shahs having a collection of rare animals and possibly some taxidermy, the likelihood of Shah Tahmasp having a zoo is very small, particularly early in his reign when the Shahnama was being produced. Thus, for certain non-indigenous or dangerous animals, the artists of the Shahnama were probably not relying on living models but instead turned to prototypes in the Safavid royal library.

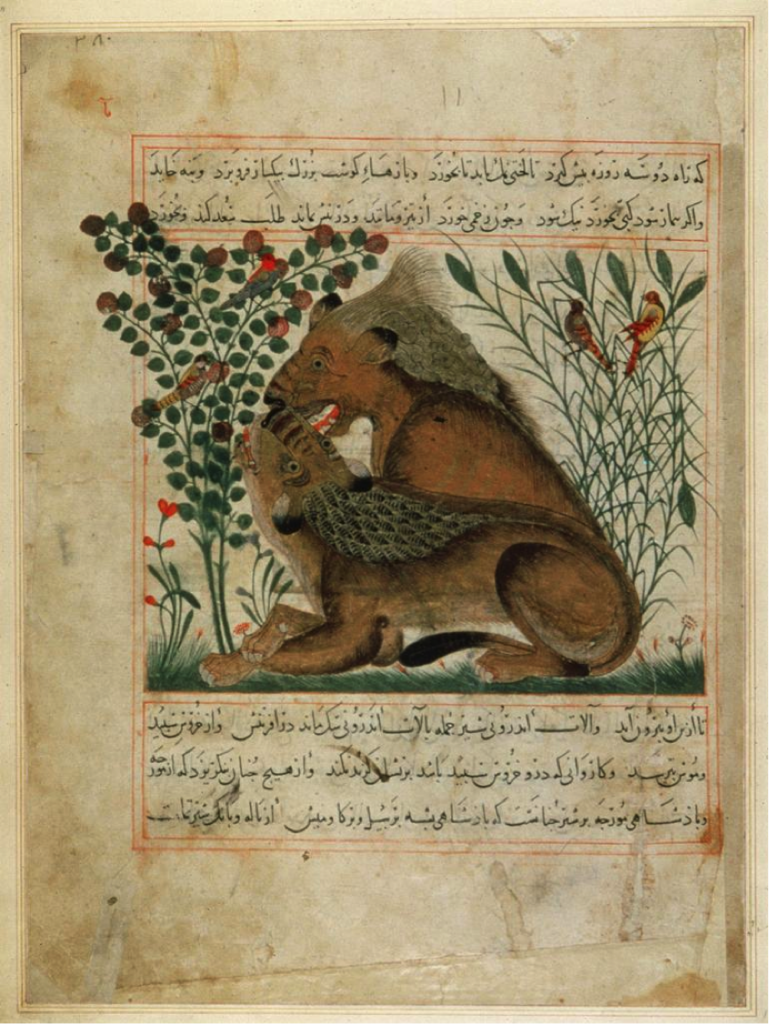

Lions, on the other hand, were indigenous to Iran, but posed as they are in the painting, with one lying and one seated and roaring and one male, one female, are more likely based on a pictorial prototype. A comparison with a famous image of a pair of lions from the Manafi al-Hayawan of Ibn Bakhtishu from 1297 or 1299 (Fig. 6) with the lions in the Court of Gayumars reveals some congruities of pose with some interesting divergences. The 13th century manuscript was produced at Maragha, near Tabriz. However, its later history does not support the notion that Sultan Muhammad would have seen it in the royal library since it contains the seal impression of the Ottoman Sultan Bayezid, who ruled from 1481 to 1512. Even so, such figural groupings would have been reused and manipulated over the 200-plus years that separated the Manafi‘ al-Hayawan and Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama. Dickson and Welch have published two images, one from a Timurid Khamsa of Nizami of 1445 and another from one of the Istanbul albums containing variations of this same grouping of lions.[7] Each artist has modified the poses to fit his needs, just as Sultan Muhammad has interwoven the lions’ tails and turned the head of the presumed male so he can roar.

Whereas the pair of lions discussed here are based on a suite of prototypes, the male lion and the cub it faces in the arms of one of the men in the lower right of the picture are less likely to have been borrowed from an earlier composition. Instead they spring from the artist’s imagination and interpretation of the context of this episode. Likewise, the gazelles that daintily clamber up the mountain, or deer that bend over to drink from a stream or sniff at each other have been rendered naturalistically, as if they were within their native habitat. Nonetheless, most of them appear in pairs, which harks back to illustrations in natural history texts such as the Manafi‘ al-Hayawan and related books. As with the lions, the pictorial sources are not always obvious, but Sultan Muhammad approaches their depiction in the most artful fashion as if they were from the repertoire of animal design rather than as individualized beings. Certain animals such as the black bear hiding in the rocks at the right below the pair of lions or the leopard lying on an outcrop are alone, without a mate. Whether this is simply a compositional choice or one made with a particular prototype in mind is not entirely clear. In the 1297-99 Morgan Library Manafi‘ al-Hayawan the leopard is depicted solo as are a number of other animals,[8] whereas in one of the albums now in Istanbul but thought to have been taken there from Tabriz two leopards appear nestled in a rocky hillside in a 15th century painting.[9] As with the Shahnama painting, the leopards have been accurately depicted with spots that form circles, large heads and powerful bodies. Persian leopards live in the rocky crags of the Alburz and Zagros mountains and forests and plains far from urban centers. They prey on mountain goats, sheep, deer and onagers. While the likelihood is small that Sultan Muhammad ever saw an actual specimen in the wild, we do not know enough about his travels and life outside of the court kitab-khana to speculate on sightings of leopards.

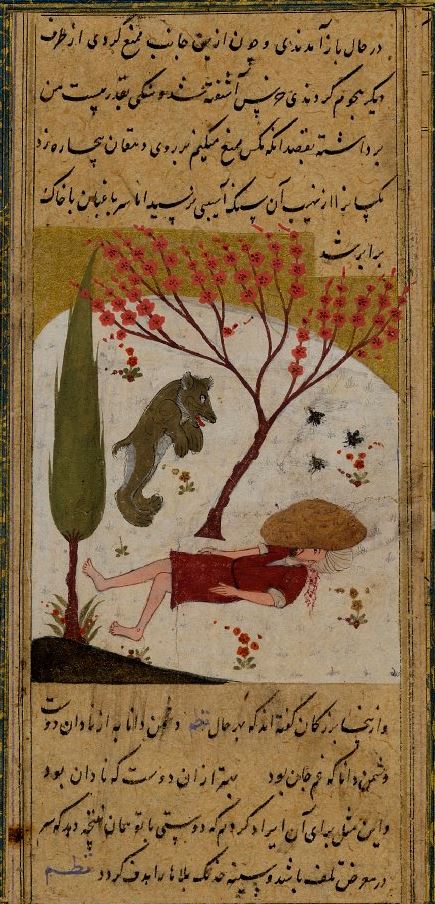

The Feast of Sadeh (Fig. 7), also attributed to Sultan Muhammad, represents the grandson of Gayumars, Hushang, who presided over the development of metalworking and animal husbandry. When he struck a boulder with a rock, causing sparks to fly and turn into flames, he understood fire as a divine gift and instituted this feast to celebrate the discovery. The domesticated animals in the foreground certainly allude to his program of farming animals, while wild animals run free in the mountains rising behind him. In the mountains at the right stands an ibex, identified by his ridged curved antlers and his black beard. He gazes across a crevasse at what appears to be the female of his species. As is typical of Sultan Muhammad, the female ibex above Hushang strikes an animated pose, scratching its neck with its back hoof. Compared to photographs of the Nubian ibex which inhabits the mountains of Western Asia, these two creatures have a whiter chest and more delicate build. Also, the female would be quite immature since ibexes sprout horns quite early. Thus, in his rendering of these ibexes the artist strikes a balance between naturalism and subtle artistic license. Above the male ibex, two chukar partridges, one hidden behind a rock, are engaged in conversation. These birds would have been widely distributed across Europe, Western Asia and South Asia, where they became a popular subject in Mughal painting at the end of the sixteenth century. The vignette to the right of the partridges in which a bear prepares to launch a large rock at the leopard lying below it comes from an altogether different source than the actual sighting of native animals in their habitats. Although it is unclear how early this theme enters the corpus of Persian painting, by the second half of the fifteenth century one can find a Turkman painting in which a bear on a mountain top prepares to hurl a boulder on a leopard lying below. It is possible that the idea, though not necessarily the composition, originated with a story from the Anvar-i Suhayli, a variant of the fables of Kalila wa Dimna, where a bear returns a man’s act of kindness by swatting a fly on his face with a boulder, which kills the man (Fig. 8). By the first half of the sixteenth century this motif had lost whatever specific narrative meaning it had once had and entered the class of animal design described by Sadiqi Beg. Thus, it joins the combats of phoenix and dragon, lion and deer, and other contests between animals that adorn textiles, carpets, bookbindings and decorative borders of manuscripts.

Along the lower edge of the illustration appear a number of animals that were domesticated and some that were not. At the right a red deer with a magnificent set of antlers turns back toward his doe, while at the lower right edge a pair of young deer peek out behind the rocks. These, of course, are animals that never were domesticated. Likewise, even though a man is holding a leopard cub with a collar, the only big cat that was partially tamed was the cheetah, used in hunting. The dark grey cat in the arms of another figure may have been a regular domestic cat, but the fox that a boy grasps at the left is also wild. Moving to the left along the lower edge of the image, we see a herdsman with four goats and a mouflon sheep with s-shaped horns and at the far left a bullock and cow and a mule braying. Although Mouflon sheep appear on Sasanian dishes of the fifth -sixth century, they are shown hunted in the wild. Interestingly, they are considered the ancestors of domestic sheep, but the appearance of the mouflon in this painting may have more to do with Sultan Muhammad’s desire to suggest the transition from wild to domestic that took place during the reign of Hushang. If that is a subtext of this painting, the range from wild to tame would occur across the lower edge of the image from right to left.

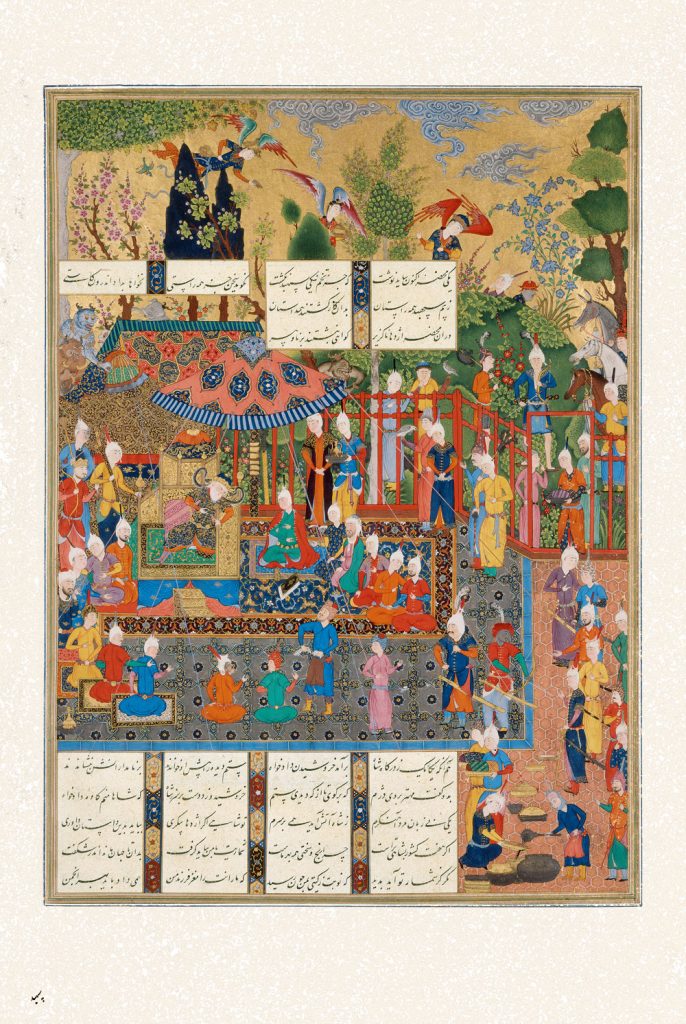

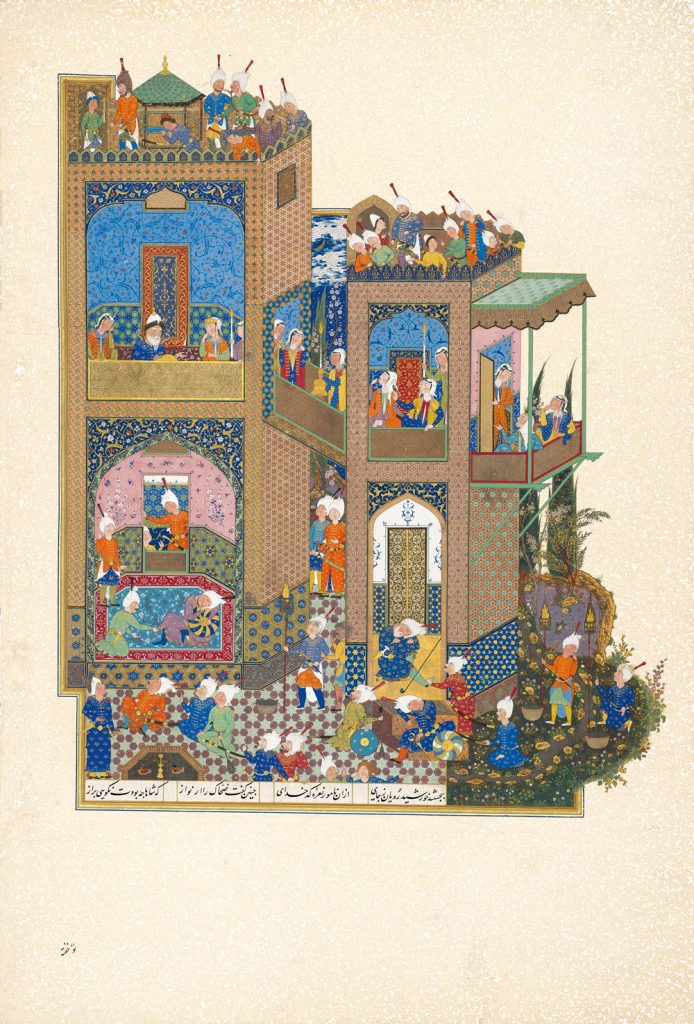

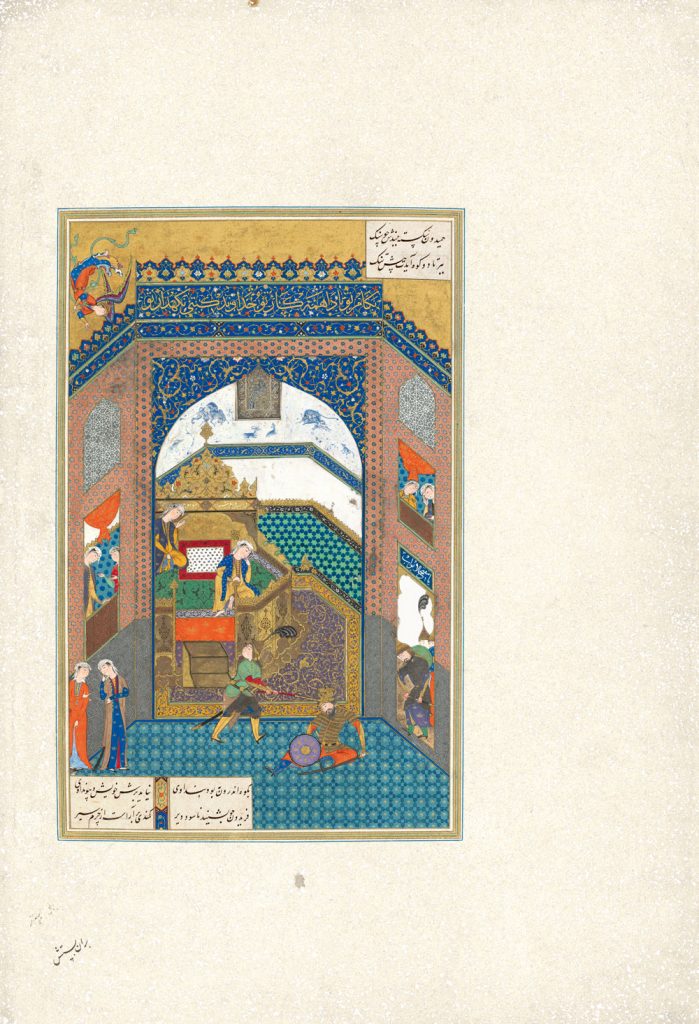

In the illustration of Kava tearing Zahhak’s scroll (fig. 9) , the blacksmith Kava tears up a scroll that the evil king Zahhak had forced his noblemen to sign, falsely attesting to his just and honest rule. Earlier when Zahhak made a deal with the devil, two serpents sprouted from his shoulders. In order to avoid being poisoned by them, Zahhak had to feed them the brains of Iranian youths every day. As a result, all of Kava’s sons were murdered by the king’s men, leading to his protest against Zahhak. As in the other Shahnama illustrations the main action occurs in the middle and foreground of the setting, while humans and real and fantastic creatures populate the rest of the page. At the right, outside the fence stand two horses and a mule with young grooms. In the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp mules are associated with figures on the fringes of the narrative, not the protagonists. Likewise, donkeys, distinguished by their smaller stature, serve only as beasts of burden. To the proper left of Zahhak and his courtiers two falconers stand with hawks resting on their gloved hands. The larger one with its white belly and head is most likely a saker falcon while the smaller one with yellow feet appears to be a lanner falcon. Falconry had a long history in Iran as a popular sport. The Safavid court employed royal falconers (qushchi) to train and care for the birds, which were used for hunting other birds and small to medium sized game. The hunt would take place when the falconer was on horseback and could release his bird to soar high before attacking its prey. While Shah Tahmasp preferred fishing to hunting, his father, Shah Isma‘il, had been an avid hunter and in the last decade of his rule devoted himself almost full time to the hunt. Finally, in this painting note the creatures at the left of Zahhak’s tent, the divs. These ghoulish figures, including an elephant-headed demon with horns sprouting from its head, do not really fall into the category of Iranian wildlife since they are a figment of poetic and artistic imagination. However, in many paintings in this manuscript they embody the playful, naughty spirit of beings that the early kings of Iran, though not Zahhak, had to subdue.

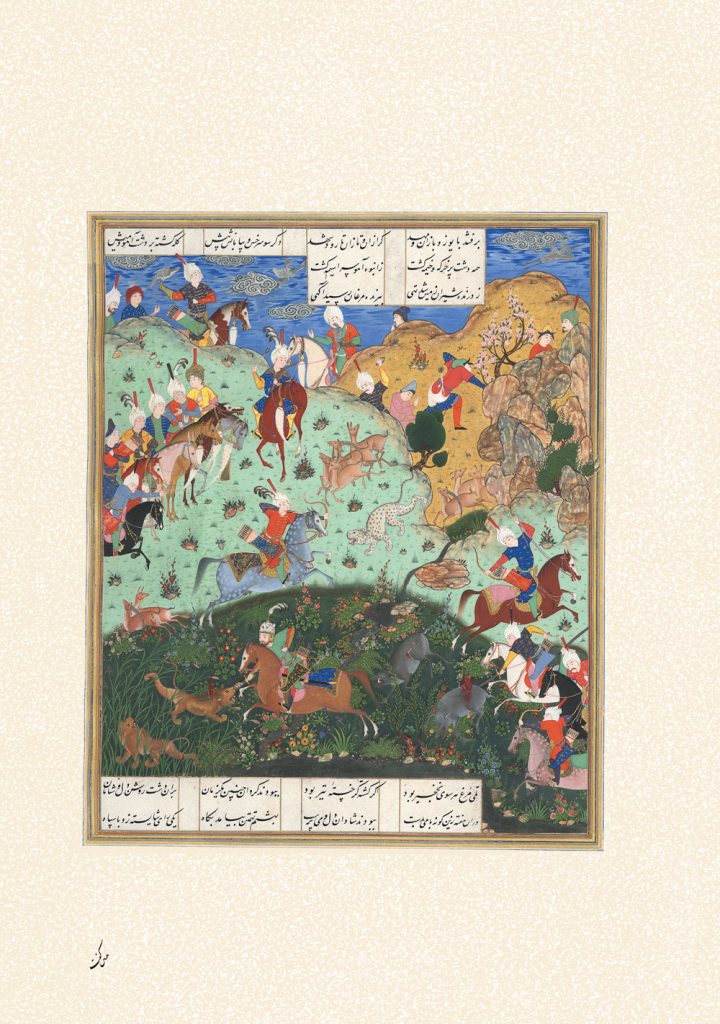

In Rustam and the Seven Champions of Iran Hunt in Turan (fig. 10), attributed to the artist Mir Sayyid `Ali, the most prominent hero of the epic, Rustam, slashes a lion with his sword in the center of the composition. To the right hunters shoot wild boar with arrows and attack them with swords. Not only are wild boars native to Iran, but they figure in several famous hunting episodes in the Shahnama. This one revolves around the trespass of Rustam and the champions on the territory of their arch-enemy, the Turanian Afrasiyab. Another concerns a herd of wild boar that were destroying the fields and flocks of a distant land. The young hero Bizhan pursued the boars and polished off their leader, which caused the others to disperse. Like the mouton sheep, boars also appear on Sasanian metalwork, attesting to their perennial popularity as prey in the hunt. While we have no way of knowing whether the artist ever saw a boar in the wild or on a Sasanian metal bowl, he may well have visited or known of Taq-i Bustan, the 4th century site of royal Sasanian relief carvings near Kirmanshah. Even the diagonal poses of the boar in the painting recall the placement of the boar in the stone relief. Interestingly, boar do not appear in the albums that include so many animal drawings and Chinese-style fantastic beasts. Rather, they are one of the animals included in the encyclopaedic text, the Wonders of Creation, by the 13th century cosmographer, Zakariyya ibn Muhammad Qazvini. Thus, the artist’s familiarity with the animal did not require first-hand experience of a live specimen, only knowledge of visual sources in one form or another. With the lions, numerous pictorial prototypes existed from illustrated books, albums, portable objects and probably wall paintings that have since disappeared. What is particular to this picture is that they are in a bed of reeds. Lion hunting itself, of course, continued in Iran for centuries after this painting, but it also was a very popular sport of the sultans and maharajas of India. Mir Sayyid `Ali emigrated to the Mughal court in India and under Akbar in the late 1550s or early 1560s helped found the Mughal school of painting. Admired by the Mughals for his naturalism and attention to the accurate depiction of people and things, Mir Sayyid `Ali also imported motifs from Safavid painting to India. In an image from the Dastan-i Amir Hamza, or Hamzanama, a manuscript of which Mir Sayyid `Ali was the supervisor, Hamza attacks a tiger in the reeds in much the same way as Rustam slices the lion in the Shahnama page.[10] Although the species is different, the notion of attacking a big cat in the reeds is the same and one that remained current in India painting for at least two hundred years.

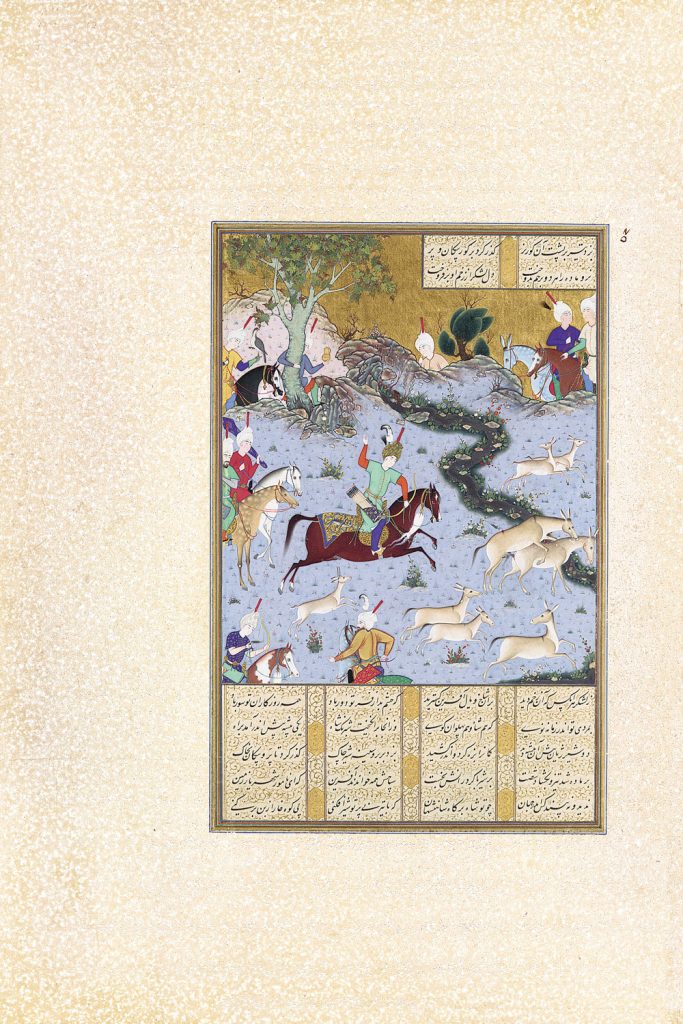

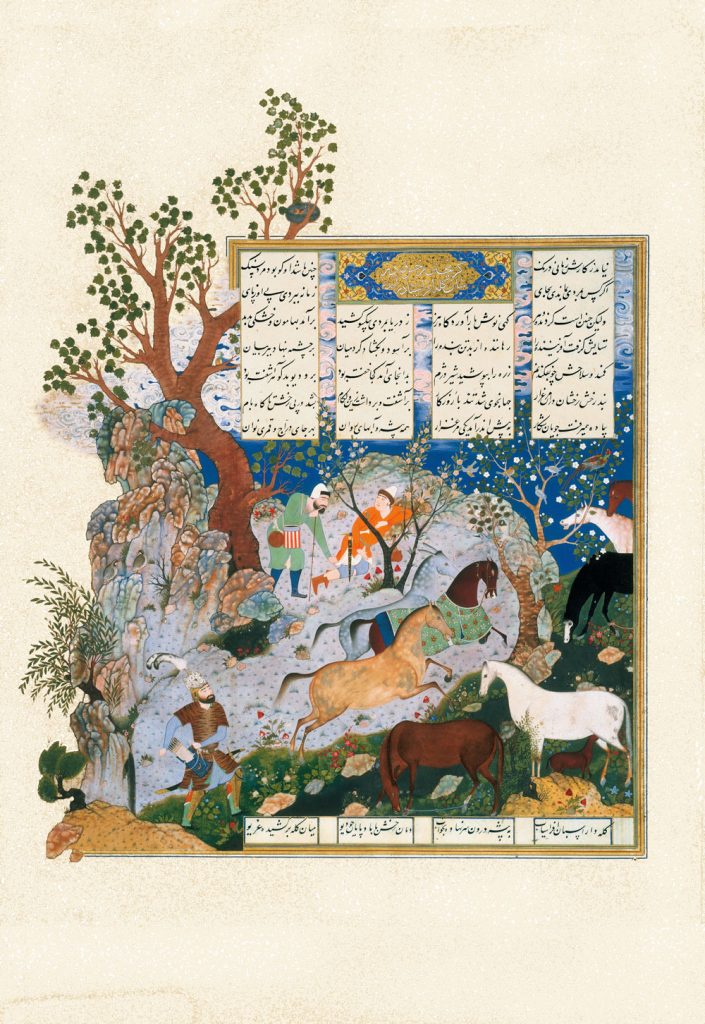

One of the native Iranian species that finds its way into both the stories and the illustrations of the Shahnama is the onager, or wild ass. Numerous hunting scenes included these animals that are pursued along with gazelles, deer and lions. One of the most celebrated hunters in the Shahnama was the Sasanian king Bahram. In “Bahram Gur Pins the Coupling Onagers” (fig. 11), he comes upon a mating couple of onagers and pins them both with one arrow, earning him the name Bahram Gur, or ‘Onagers Bahram’ since gur means onager. Unlike the donkeys that they resemble, onagers are highly resistant to taming, which one must assume is why they were hunted.

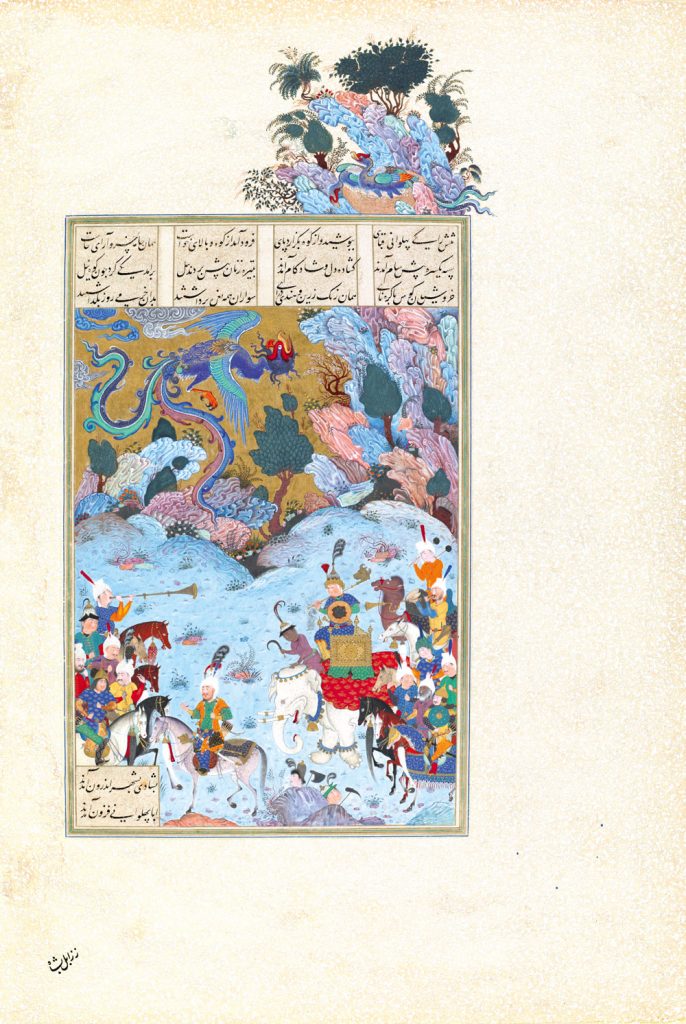

Not all animals in the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp are what we would call real. The simurgh was a magical bird that enters the narrative of the epic as the savior of the infant Zal, whose father Sam had ordered that he be abandoned on Mount Alburz because he was albino, considered a bad omen. The simurgh, whose nest was at the top of the mountain, heard Zal’s cries, scooped him up and carried him to her aerie where she nurtured him with her own young. Passersby reported seeing a white haired child high on the mountain and word eventually reached his father. Sam convinced the simurgh to return Zal to him and as he was leaving, she gave Zal a feather to burn if he ever needed her help. In ‘Sam Returns with Zal’ (fig. 12), the young Zal rides in a howdah on the back of an albino elephant while his father rides a dappled grey horse ahead of him. Until the second century BC either Indian elephants or a western cousin, called a Syrian elephant were extant in Iran. Elephants apparently continued to be used for both war and hunting in the early centuries AD since the reliefs at Taq-i Bustan include a massive hunt with the hunters on elephant-back. In the Islamic period, elephants were presented to the caliphs as diplomatic gifts but mostly they were an object of curiosity. Representations of elephants in the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp usually include details such as the small ears with uneven edges. While Asian elephants have much smaller ears than their African cousins, their jagged contours are exaggerated in the painting. In battle scenes, the leaders of opposing armies ride elephants while the rest of the army is depicted on horse or camelback. A rather tentative fifteenth century drawing from the Diez albums shows a war elephant with very small ears and a rather awkwardly drawn head, but with a bell around its neck.[11] Similarly, Zal’s elephant has a collar with a large bell and other ornaments. Presumably, elephants were prized and rare and deserving of jewelry in recognition of their value. The youth with a goad riding behind the elephant’s head is dark-skinned, an indication in Persian painting of Indian ethnicity, which would be fitting here because the elephant would have been perceived as Indian. Interestingly in the text describing the reunion of Sam and Zal, Sam brought a horse and royal clothes for Zal and elephants led the procession bearing drummers.

As for the simurgh, with the invasion of the Mongols in the 13th century the form of the simurgh changed from a dog-faced winged creature with a bird’s tail to the Chinese-inspired phoenix shape with long snaking tail feathers and a raptor’s head and beak. The revived interest in chinoiserie in the fifteenth century reinforced this imagery as found in a design for a textile from one of the albums demonstrates.[12] Like dragons, simurghs appear on a whole range of decorative arts where their meaning is no longer tied specifically to the magical bird of the Shahnama but instead has more general positive connotations as the primary opponent of the dragon, a negative force.

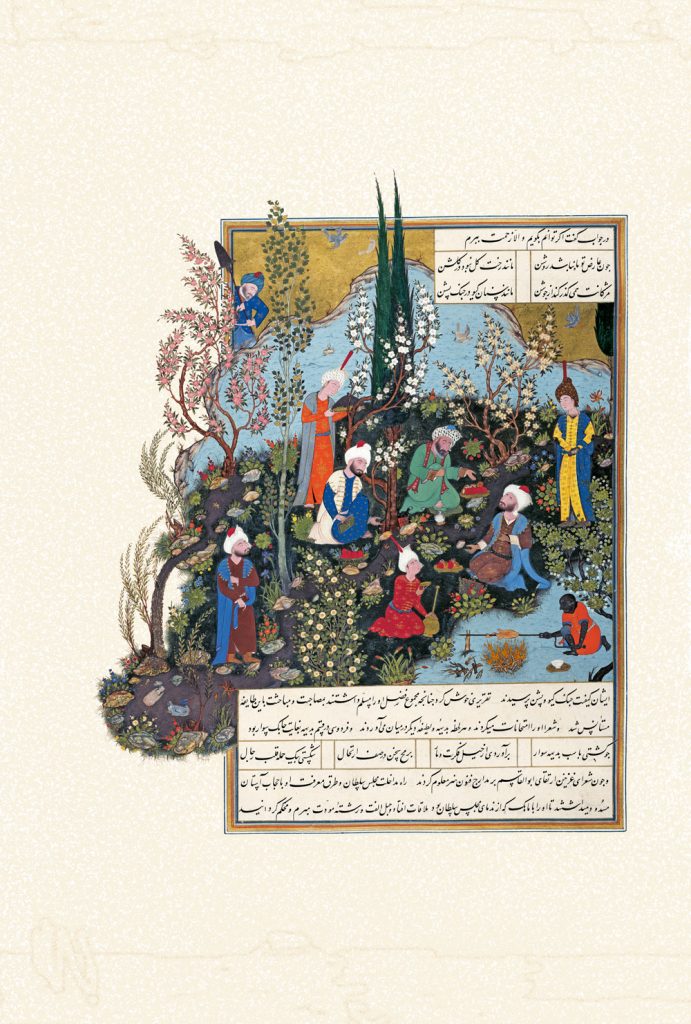

The first illustration of Tahmasp’s Shahnama depicts its author Firdausi and the three poets of Ghazna (fig. 13). Firdausi, standing at the left, had come to Ghazna to seek the patronage of Sultan Mahmud, but before he could gain access to the court, he had to prove himself by completing a couplet devised by the poets, here seated on the ground having a picnic. Set in a country garden, the scene is full of flowering trees, shrubs and plants, all of which tell the viewer that it is springtime. Although no large animals are present, a pair of ducks swims in the pool at the lower left. Despite its blue head and red beak, the duck to the right is most likely a male mallard accompanied by its mate diving into the pool at the left. Iran apparently has thirty-three different kinds of ducks but apparently none that have blue heads and red beaks. This begs the question of whether the artist, Aqa Mirak, altered the plumage of the duck in the interest of color harmony with the rest of the composition. Certainly he would have been no stranger to mallard ducks, but as we have seen in other paintings, the artists of the Shahnama did not hesitate to adapt the shape or color of the animals they depicted to achieve the desired result in their compositions. Ducks were also a common subject in 15th century drawings placed in albums and were a staple of the decorative repertoire in the 16th century as well.[13] In the fifteenth century cloud collar design the artist has included a variety of birds in the duck family including a pair of pin-tails and long-necked varieties. At the top of the drawing a pair of ducks sail along in much the same way as the mallard in the Shahnama painting. Although we do not know a great deal about the training of Safavid artists, Sadiqi Beg in his Canons of Painting mentions Aga Mirak as the ‘true pearl of the Sea of Marvels’ who understood the distinction between suratgari, or figural painting, and janvar-sazi, animal design. In figural painting, the artist’s work would be based on the direct observation of Nature whereas in animal design ‘artful imitation’ of past models was required. In fact, the detail of the ducks in the Shahnama illustration appears to combine both principles, since the artist could have copied any number of drawings of ducks, yet he chose to adapt his painting to his own compositional needs.

At the top of the image, four birds – two gray and two white – appear to be some form of lark or warbler with certain peculiarities that again point to the artist’s choice rather than ornithological precision. Three of the four birds have red beaks and legs, while the right-hand white one, which appears similar in every other way to white bird in the cypress tree, has black legs and a brown or black beak. Instead of pairing them off by color, Aga Mirak has associated the grey birds with the white ones, again deviating from the male-female match-up that occurs in the rendering of many wild animal species in the Shahnama illustrations. In this painting, Aqa Mirak has included the birds to provide vignettes of variety and animation rather than slavishly following the patterns of his predecessors.

In ‘Rustam Recovers Rakhsh from Afrasiyab’s Herd’ (fig. 14) we encounter a number of birds that are more easily recognizable than in the previous painting. Above Rustam’s head, two chukar partridges are perched on a rocky outcrop, while a nest high in the plane tree contains two chicks. They may be the young of the pheasant perched in the tree at the right and turning its head back, but even that mature bird appears to be an amalgam of the Asian golden pheasant and some other type. Two other pairs of smaller birds perch or flutter around the flowering tree. Although they might be recognizable, the grey ones have a black band around their necks and the others combine rufous head and body with grey wings, they remain to be precisely identified. Aside from their coloring, their size may have been manipulated in the interests of the composition. Rather than provide precise information about the birds, the artist may have included them to augment the image of a springtime setting in the mountains.

At one point in the epic Rustam falls asleep near the lair of a demon, the div Akvan, who picks him up and offers him the choice of being smashed on the rocks of a mountain or thrown into the sea. Rustam chooses the rocks, knowing that the div will do the opposite. During the time that this takes, Rustam’s horse Rakhsh wanders off and joins a herd of horses that turns out to be that of his arch-enemy Afrasiyab. Rustam tracks down Rakhsh and eventually lassoes him and rides away. When he does this, the whole herd follows. Rakhsh represents a different category of animal portrayed in the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp. Instead of being a generic form of a particular species, Rakhsh is an actual character in the story whose actions have consequences for the plot. Although the depiction of many of the human and animal figures in the manuscript is inconsistent, the costume of the adult Rustam and the appearance of Rakhsh are uniform. When as a young, but already exceptionally large and strong man, Rustam was taken by his father, Zal, to choose his steed, the horse he spotted was only a colt. Nevertheless, Rakhsh also was unusually large for his age. The Shahnama describes him thus:

Among them a grey mare short-legged and fleet,

With lion’s chest and ears like two steel daggers,

Her breast and shoulder full and barrel fine.

Behind her came a colt as tall as she,

His buttocks and his breast as broad as hers,

Dark-eyed and tapering—a piebald bay

With belly hard and jet-black, hoofs of steel,

His whole form beautiful, and spotted roan

Like roses spread upon a ground of saffron.[14]

In this painting, despite some discoloration, the markings on Rakhsh are evident as are his black hooves. The dark brown horse next to him is covered with a decorative blanket that must have been intended to indicate his status as part of the royal herd of Afrasiyab. The allegiance to the text weakens a bit with the inclusion of two tethered horses that might or might not have been able to follow Rustam and Rakhsh as they rode away. However, for the purposes of this painting, they support the impression of a herd grazing in a mountain pasture.

The final category of animal depiction in Tahmasp’s Shahnama is the appearance of animals in the wall paintings of architectural settings. Perhaps the only instance of an insect occurs in the ‘Nightmare of Zahhak’ (fig. 15), an episode in which the evil king Zahhak dreams that he will be killed by someone bearing a bull’s headed mace. He wakes up screaming, disturbing the slumber of everyone in his palace. The wall of an ivan, or niche, on the ground floor of the palace, has been decorated with vegetation and what may be dragonflies or butterflies fluttering past small clouds and flowering plants. Except to convey a sense of springtime, the flowering plants and insects probably have no more developed symbolism. Yet, given the rarity of butterflies and dragonflies in Persian painting, one must ask how they came to appear here at all. Turning to the Istanbul albums again, we find a group of works that are closely based on Chinese prototypes rather than simply Chinoiserie exercises borrowing Chinese forms. Thus, bird and flower images often include butterflies with long tails like those in the Shahnama painting.[15] Unlike ducks and dragons, butterflies did not enjoy much currency in early sixteenth century Persian painting but were revived in the late seventeenth and eighteenth century, when they appear on floral borders in manuscripts and on lacquer bindings featuring the rose and the nightingale.

Another more typical form of animal decoration on walls in the Shahnama is the animal combat. In Faridun Strikes Down Zahhak (fig. 16), the wall above the throne includes two vignettes of a lion attacking another animal, a bullock on the left and a stag on the right. In the center of the wall between them are what appear to be a mouflon sheep and its mate, while on either side two jackals watch the action. Unlike the previous wall painting, the subject matter of this one, which is the power and dominance of the king, that is, the king of beasts, reflects that of the scene below where the divinely ordained Faridun lands the fatal blow of his ox-headed mace on the head of Zahhak. Also, in contrast to the wall painting with butterflies, this iconography has a very long history in Iran, from the walls of the Apadana at the Achaemenid Palace at Persepolis from the fifth century BC to the 1429 Timurid Kalila wa Dimna. In fact, although the bull in the wall painting is not flipped over as in the Kalila wa Dimna image, the two jackals on either side may reflect the placement of the jackals Kalila and Dimna in the manuscript. The desirable traits for animal combats are described by Sadiqi Beg, who calls the motif, “girift-o gir which is to say the give and take of animals locked in battle. In connection with this… there are three pointers…: First, you must at all costs avoid any bodily slackness in your figures; in particular, the shanks of the hooves or paws must be drawn taut. Secondly, when two animals are designed in clawed combat, both bodies must be shown wholly at grips with one another…The third pointer is the undesirability of repeating identical patters – indeed, what is required is the very antithesis. It is true that repeating a pattern may have some magical appeal; but, by nature this palls and becomes all monotonous.’[16] Thus, Sadiqi Beg explains the fine line for the artist between tedious repetition of motifs and variations on a theme.

To sum up, the illustrations of the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp contain a whole cast of supporting characters in the form of animals. Some are domestic, some are wild, some fly, some swim and some are earthbound. Whereas horses are the most populous, appearing in well over half the illustrations, many other animals are dotted through the manuscript either as background details or protagonists in their own right. The images in the manuscript run the gamut from those in which artists employed naturalism in their depictions of animals to others in which the artists looked to examples in fifteenth century albums and illustrated manuscripts for inspiration. In part, this may have been the result of unfamiliarity with various species such as elephants, lions and bears and the need to understand their behavior. However, the respect for one’s forebears in the chain of transmission of artistic ideas was well established by the early sixteenth century. Thus, the paintings weave together empirical observation with ideas derived from pictorial sources to produce a world inhabited by animals which most often remain ‘anonymous’ but enliven compositions dominated by men. Whereas the clothes and accoutrements of the figures in the paintings reflect the period in which they were produced, not the prehistoric and pre-Islamic material world of Iran, the animals hark back to traditions of ancient Iran and motifs of the fifteenth century and earlier, many of which derive from Chinese prototypes. The tension in the manuscript between realism and artistic license or imitation of pictorial sources complicates our understanding of the illustrations, where a great deal happens that is seemingly unrelated to the narrative. Yet, the relationship between man and beast in Tahmasp’s Shahnama provides an insight not only into art but also into the environment of Iran in the preindustrial era, namely all of its history until the nineteenth century.

Figures

Footnotes

[1] This paper is based on a lecture I gave at the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha in 2015. The topic seemed like a natural one for a volume dedicated to Holly Davidson who has infused the study of the Shahnama in North America with her enthusiasm and knowledge, introducing Firdausi’s epic to many who would have remained ignorant of its greatness without her work.

[2] Martin Bernard Dickson and Stuart Cary Welch, The Houghton Shahnameh, 2 vols. (Cambridge, MA: 1981).

[3] Sheila R. Canby, The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: The Persian Book of Kings (New York: 2011 and 2014).

[4] A. H. Morton in Michele Membré, Mission to the Lord Sophy of Persia (1539–1542), trans. and intro. A. H. Morton (London: 1993), p.23.

[5] The Canons of Painting by Șādiqī Bek, in Dickson and Welch, vol. I (1981), p. 264.

[6] B.W. Robinson, “Prince Baysunghur and the Fables of Bidpai”, Studies in Persian Art, vol. II (London: 1993), 128-137, especially figs. 3-8. The manuscripts are now in the Topkapı Saray Library, R.1022 and No. 867.

[7] Dickson and Welch (1981), vol. I, figs. 20 and 21.

[8] Barbara Schmitz, Islamic and Indian Manuscripts and Paintings in The Pierpont Morgan Library (New York: 1997), cat. 1, fol. 18r, pl. 3.

[9] Mazhar Ş. Ipşiroğlu, Siyah Qalem (Graz, Austria: 1976), no. 71, Topkapı Saray Library, H.2160, fol. 84a.

[10] Susan Stronge, Painting for the Mughal Emperor: The Art of the Book 1560-1660 (London: 2002), p. 26, plate 11.

[11] http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN73601389X&PHYSID=PHYS_0032&DMDID=DMDLOG_0032, Diez A, Fol. 73, S. 9, Nr. 6, accessed 12/27/17.

[12] http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN73601389X&PHYSID=PHYS_0166&DMDID=DMDLOG_0166, Diez A, fol. 73, S. 63, Nr. 2, accessed 12/27/17.

[13] http://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN73601389X&PHYSID=PHYS_0095&DMDID=DMDLOG_0095, Diez A, Fol. 73, S.45, Nr. 1, accessed 12/27/17.

[14] http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main, The Shahnama of Firdausi, vol. 1, §2, v. 287, accessed 12/27/17.

[15] Ernst J. Grube and Eleanor Sims, eds., Between China and Iran: Paintings from Four Istanbul Albums (London, 1985), fig. 136, H. 2153, fol. 147v.

[16] Sadiqi Beg, trans. Martin B. Dickson in Dickson and Welch (1981), vol. I, p. 265.