Opening the Door to Muslim Women Scholars and Activism at Brandeis

I’m not sure how I first met Holly Davidson but it had something to do with the fact that she was teaching a course at Brandeis on the topic of “Women in the Muslim (or perhaps it was Arab) World.” At the time I was Brandeis’ Potofsky Professor of Sociology and the Director of the Women’s Studies Program. My colleagues and I in Women’s Studies sought to introduce gendered courses into a broad array of academic departments. Holly’s work fit right into that framework. Even after she finished teaching within the Department of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies, I remember working to fund her course after the original funding ended.

After meeting her, I invited Holly to become an active member of what we called the Women’s Studies Program Community that was made up of interested faculty, students, and staff. At the end of each year at the Women’s Studies Program Commencement ceremony, each student received her/his certificate from her/his primary faculty advisor.

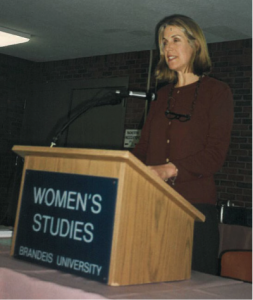

The Women’s Studies program also held an annual event where Women’s Studies faculty presented books they had recently published.

During mid-1990’s, “Women in the Moslem World” was exotic and seemingly remote topic for a course. The major Middle East wars in which the U.S. would participate had just begun. In 1987-88, the U.S. was involved in the Persian Gulf; in 1991, the U.S. homeland was attacked by forces of Osama bin Laden; the U.S. fought the Gulf War against Iraq in 1990-1991; the War in Afghanistan lasted officially from 2001-2014 but is basically continuing; the Iraq War is considered to have lasted from 2003-2011 and is also not resolved; the war in Pakistan is officially listed as 2004 – present; and the war on ISIL is labeled as 2014 to the present. All of these encounters between the U.S. military and allied forces including local populations necessitated some understanding of the status of men, women and children. So, too, did Moslem terrorist acts in the U.S., Europe and Africa.

All of these activities required understanding that Islam was not a unified perspective but had numerous subgroups and internal divisions. We in the U.S. probably all remember how unprepared the U.S. population was for these military interventions – we had very few Arabic speakers in the State Department or in the armed forces. Our college campuses had also not begun to pay attention.

Although Holly’s scholarly work dealt more with Persian literature than with contemporary political and military studies (Poet and Hero in the Persian Book of Kings; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, 1994), she was one of the first at Brandeis University to open students’ minds to the worlds of North Africa and the Eastern end of the Mediterranean, when, from 1992 to 1997, she chaired the Concentration in Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies. Holly introduced us to the significance of thinking about the Middle East and its Moslem populations in a way that now seems self-evident. Because of her continuous reminders that “attention must be paid,” as Arthur Miller wrote in Death of a Salesman, I began to use my faculty and program positions as a vehicle for bringing Muslim voices to the Brandeis campus, in partnership with Holly.

One of our first accomplishments was an invitation to a group of Iranian Muslim women journalists to speak to a small gathering of women faculty and students. The journalists spoke to us at length about how their openness would undoubtedly lead to their being unable to return to Iran.

We also brought Giselle Littman, known as Bat Ye’Or (daughter of the Nile river, Heb.), the penname of Gisèle Littman, a scholar of the history of religious minorities in the Muslim world and modern European politics. Ye’or has popularized the term dhimmitude in her books about Jews living under Islamic governments. Ye’or describes dhimmitude as the “specific social condition that resulted from jihad,” and as the “state of fear and insecurity” of “infidels” who are required to “accept a condition of humiliation.”[5] She has also popularized the term Eurabia in her writings about modern Europe, in which she argues that Islam, anti-Americanism and antisemitism hold sway over European culture and politics as a result of collaboration between radical Arabs and Muslims, on one hand, and fascists, socialists, Nazis, and the antisemitic leaders in Europe on the other. At the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, a research center I founded in 1997 that examines the intersection of Jews and gender, we held a full-day symposium on Jewish women in Moslem lands. And a few years later, we initiated a large project titled Gender, Culture, Religion and the Law, headed by Dr. Lisa Fishbayn Joffe. None of these activities were the direct result of my relation with Holly, but it is clear to me that Holly opened the door.

At Brandeis, as is true in many universities throughout the world, especially after 9/11, people wanted to learn as much as possible about the new powerhouse in the Middle East, i.e. the Moslem world. If possible, we wanted some of this learning to occur through face-to-face interaction rather than exclusively through classroom instruction. At that point the only option at Brandeis was for individual students to study abroad in a Muslim dominated society. In 1998, however, Brandeis University and Al Quds (the Arabic word for Jerusalem) University developed a kind of sister institution relation when Jehuda Reinharz, President of Brandeis and Sari Nusseibeh, President of Al Quds created the ´Brandeis-Al-Quds Partnership.’ In 2008 and 2009 Brandeis and Al Quds students met in Istanbul as part of the Brandeis-Al-Quds Summer Institute to discuss the theoretical concept of a ´good society´ through literature, political documents, and travel journals. In May 2009, a Brandeis delegation of four undergraduates and eight faculty members visited Al Quds University to strengthen the partnership and explore future cooperation. I was part of the original delegation to explore the possibility of a partnership; and I was part of a later group visit to discuss teaching methods. Although the formal relation ended in 2013 “following a Nazi-themed demonstration at Al Quds by Islamic Jihad and a widely criticized response from the Al Quds University administration,” the informal relation continues via personal ties. For example, in 2016-2017, Dr. Dan Terris, Director of the Center for Ethics, Justice and Public Life at Brandeis, is spending the year at Al-Quds as a Fulbright Scholar.

On March 23, 2005, the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism, an offshoot of the Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center, brought former Wall Street Journal reporter Asra Nomani to Brandeis University to give lectures and lead prayer services. She spoke about her career in journalism, about the beheading of her close friend and fellow reporter Daniel Pearl, and about her quest for Muslim women’s rights. Nomani, one of Pearl’s best friends, was living in Pakistan when Pearl was kidnapped. Devastated that men acting in the name of her religion had brutally killed her friend whose last words were, “I am a Jew”— Nomani was spurred on to share her personal odyssey to discover the “truth” about Islam.

Author of Standing in Mecca: An American Woman’s Struggle for the Soul of Islam, Omani led two traditionally forbidden mixed-gender prayer services at Brandeis—one inside the Brandeis Women’s Studies Research Center and the other outdoors as show in the photograph above. In a dramatic announcement at Brandeis, she stated that she was embarking on the “Muslim Women’s Freedom Tour,” advocating for an Islamic Bill of Rights for women in mosques and another for women in the bedroom.[1]

The first Imam appointed to serve the needs of the approximately 250-strong Muslim student body at Brandeis was Lebanese-born Tall Eid. Imam Eid earned a degree in Islamic Law (sharia) from Jamia al-Azhar University in Cairo in 1974, and in 2005, he received his Doctor of Theology degree from Harvard Divinity School. In 1982, Eid became the spiritual Director of the Islamic Center of New England, and as the Imam of Quincy Mosque in Quincy, Massachusetts. In February 2006, Brandeis hired Imam Eid as the first Muslim chaplain at the University. When he retired from this position nine years later, a woman Imam – Maryam Sharrieff, Interim Muslim Chaplain – replaced him. Chaplain Sharrieff works closely with the Muslim Students Association, the chaplains and others. She speaks Arabic, English, Hebrew and Italian and received her Master’s in Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School, where she concentrated on gendered Islamic studies. Her interest in the gendered “linguistic implications in the Qur’an and the Torah” and “female scholarship in Islam and Judaism” make her an excellent fit for Brandeis.

One of the goals of Muslim students and faculty at Brandeis and elsewhere is to teach people to disentangle the Muslim religion and contemporary terrorist activities undertaken in the name of Islam. This is a fraught topic. For example, Brandeis faculty member, Jytte Klausen of the Politics Department, has written extensively about this connection. Her books, The Cartoons that Shook the World (Yale University Press 2009) about the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad, and even more significant, The Islamic Challenge: Politics and Religion in Western Europe (Oxford University Press 2005), argues, on the basis of hundreds of in-person interviews, that violence is not a core element in Islam. Klausen founded the Western Jihadism Project, a data collection and archive of Islamist extremist groups in the West. Her team of Brandeis University studies Islamist terrorist networks.[2] Sadly, when Yale University Press published The Cartoons that Shook the World, they omitted reproductions of the cartoons for fear of reprisal.

A very difficult discussion about Islam and human rights occurred at the Women’s Studies Research Center, which I established in 2001. One of the visiting scholars, Dr. Tobe Levin from Frankfurt, brought an astonishing art exhibit to our Kniznick Gallery. This exhibit consisted of oil paintings by Nigerian men who were protesting the widespread practice of female genital mutilation in their country. Some of these painting had razor blades imbedded in them, and all depicted the pain and horror of the girls undergoing clitoral cutting. Accompanying the opening of this show, we organized a debate about fgm. What should have been a data-based discussion of this phenomenon turned into a shouting match between people who argued that Westerners had no right to interfere in a traditional custom in another country, and that to do so was a form of cultural imperialism. The other group sided with the African Muslim women speakers who said that to abandon these girls and women was a form of racism. It goes without saying that this “debate” was not resolved.

A review of Brandeis’ activities concerning Muslim studies, and particularly with regard to women, must include a brief discussion of the controversy that erupted when a former Brandeis university president and the Board of Trustees decided to confer an honorary degree on Ayaan Hirsi Ali.[3] The author of numerous autobiographical and analytic works on the nature of Islam, Ali is also a prominent critic of female genital mutilation. Hailed as a freedom fighter by many, she is also reviled by others as a critic of Islam. Her admirers are charged as homophobic, while her detractors are labeled as “politically correct.” In her latest book, Heretic: Why Islam Needs a Reformation Now (2015), describes recalls the incident in detail:

In September 2013, I was flattered to be called by the then president of Brandeis University, Frederick Lawrence, and offered an honorary degree in social justice, to be conferred at the university’s commencement ceremony in May 2014. …Six months later…I received another phone call from President Lawrence, this time to inform me that Brandeis was revoking my invitation. I was stunned. I soon learned that an online petition, organized initially by the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) and located at the website change.org, had been circulated by some students and faculty who were offended by my selection.

Accusing me of “hate speech,” the change.org petition began by saying that it had “come as a shock to our community due to her extreme Islamophobic beliefs, that Ayaan Hirsi Ali would be receiving an Honorary Degree in Social Justice this year. The selection of Hirsi Ali to receive an honorary degree is a blatant and callous disregard by the administration of not only the Muslim students, but of any student who has experienced pure hate speech. It is a direct violation of Brandeis University’s own moral code as well as the rights of Brandeis students.” In closing, the petitioners asked: “How can an Administration of a University that prides itself on social justice and acceptance of all make a decision that targets and disrespects its own students?” My nomination to receive an honorary degree was “hurtful to the Muslim students and the Brandeis community who stand for social justice.”

No fewer than eighty-seven members of the Brandeis faculty had also written to express their “shock and dismay”…I was a “divisive individual.” In particular, I was guilty of suggesting that: “violence toward girls and women is particular to Islam…thereby obscuring such violence in our midst among non-Muslims, including on our own campus [and] the…hard work on the ground by committed Muslim feminist and other progressive Muslim activists and scholars, who find support for gender and other equality with the Muslim tradition and are effective at achieve it.[4]

Where will Brandeis University administration, faculty and students go from here in welcoming the Muslim voice? Obviously, it is impossible to predict the future, but given Trump’s presidency, it seem unlikely that the topic will fade even as new social concerns gain attention. “Diversity” is now the focus of protests and efforts to change the campus. The term “diversity” refers almost exclusively to students of color, i.e. African-American students. I do not see much evidence that Asian students, Latino students or Muslim students are being brought in under the diversity umbrella. It is too early to tell, however, but I for one would be disappointed if all the effort to clarify our understanding of Women in Muslim Societies, the work that Holly Davidson began at Brandeis, would come to an abrupt halt.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.brandeis.edu/investigate/events/2005/nomani.html

[2] http://www.brandeis.edu/facultyguide/person.html?emplid=8cfea83c0a70191751f1d16c96473b7b95d7e0a

[3] http://www.truthrevolt.org/news/brandeis-msa-speaks-out-against-hirsi-ali

[4] Ayaan Hirsi Ali, pp. 4-5.